In the Archives: How to Photograph a Ford Car

In the late 1970s, J. Walter Thompson produced an internal manual titled How to Photograph a Ford Car to standardize the production workflow behind its automotive campaigns. Written by art director John F. Dignam, the document offers a behind-the-scenes look at how JWT crafted Ford’s advertising imagery—and at how creative labor was coordinated, controlled, and codified across shoots.

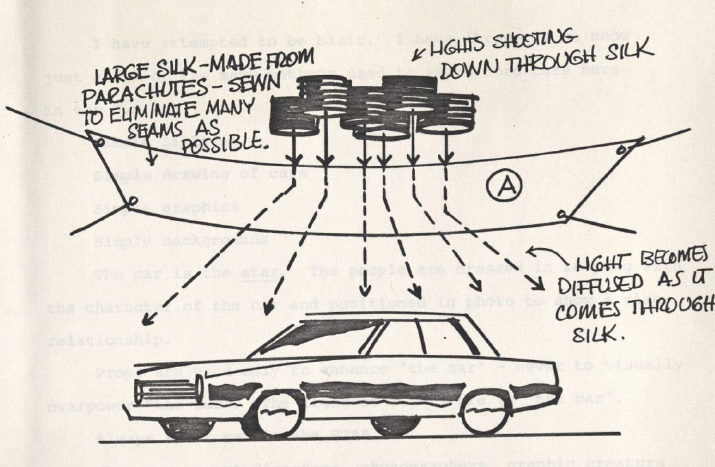

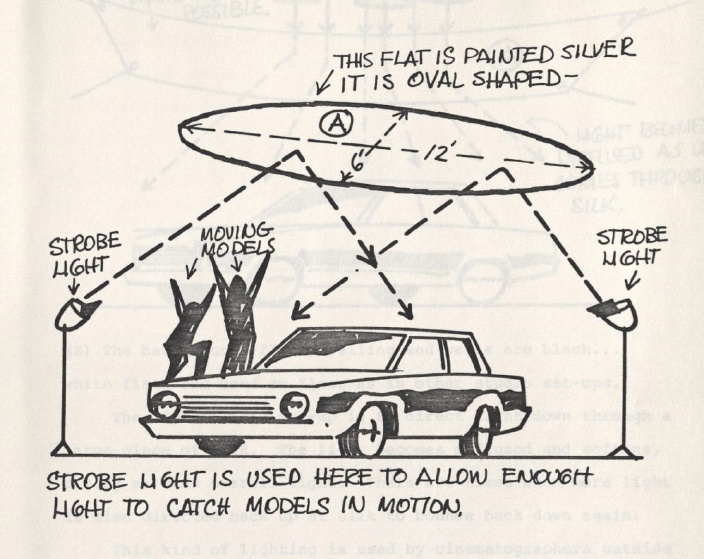

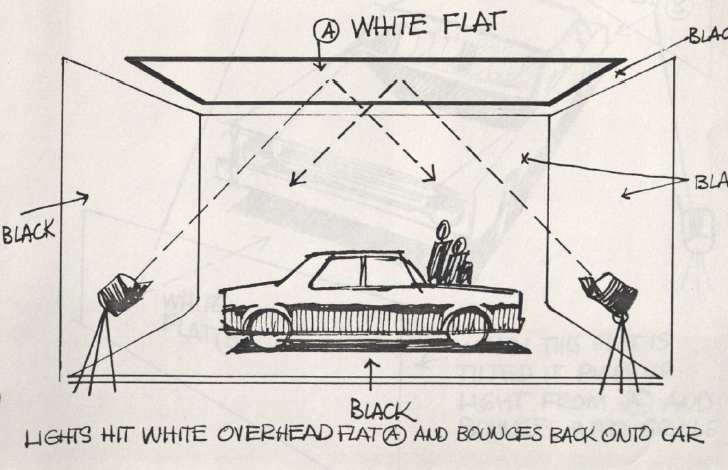

Far from a photography tutorial, Dignam’s manual is a tool of industrial design. It breaks down the prescribed techniques for creating the moods, rich colors, and crisp lines associated with Ford ads of the era. Every element—from the angle of a key light to the shape of a backdrop—is carefully detailed. And while it presents itself as a guide for best practices, the document is, more subtly, a directive: an assertion of aesthetic authority by the agency’s art department over the visual language of the brand.

Dignam is not a photographer, and he says so plainly. Yet the manual leaves little room for photographic improvisation. Instead, it emphasizes repeatability, consistency, and brand fidelity. The photographer’s job is to reproduce Ford’s established look—not to reinvent it. "Creative experimentation," here, is understood as a liability. Once Dignam and his team defined the aesthetic, the task of future crews was simply to reproduce it.

Click here to download the manual →

Held in the John F. Dignam Collection at Duke University’s Hartman Center.

What’s fascinating is how clearly this text dramatizes a key tension in the history of advertising photography: the push and pull between artistry and standardization, between creative freedom and corporate control. Dignam’s manual doesn’t just tell photographers how to light a car—it tells us a great deal about how creative labor is structured, bounded, and instrumentalized within industrial advertising systems.

The ad photograph, Dignam reminds us, is a hybrid object. It emerges from a studio, but it behaves like a product of the factory—designed for efficiency, engineered to spec, meant to perform on demand. And of course, the car is itself a hybrid: marketed as a symbol of individuality and expression, but produced within an intensely technical and hierarchical system of industrial manufacturing.

In last week’s post on Walter Herdeg’s Photographis, we saw a different model: Herdeg championed the advertising photographer as auteur—an artist whose vision shaped the look of postwar commerce. But Dignam’s manual suggests an alternate reality, one in which vision is negotiated, if not entirely pre-scripted. It raises an important question: can a single person be credited with authorship over an advertising image at all?

Dignam’s manual underscores what advertising photography often tries to obscure: that these images are collective constructions, shaped by layers of collaboration, control, and creative constraint.